The California Coast: Resilience and Adaptation Planning for Sea Level Rise

Analogies between the built environment and scientific frameworks are abundant. Likening urban systems to ecological ones is perhaps not surprising given society’s dependence on nature for its existence. In one such relatively recent turn in urban thought, the idea of resilience draws from an ecological discourse to support planning efforts that promote stability. In the face of an external threat, resilience is defined as the ability to return to a previous state or to evolve into a new state. How the system that resilience is applied to is defined, where its limits are drawn, who the actors are who fall within that system, and the timeframe in which we are seeking to intervene are all open questions. This project focuses specifically on resilience planning in the face of climate change by identifying the effect of sea level rise on the California coast.

The two primary causes for sea level rise include the melting of ice and thermal expansion. An increase in global mean temperature accelerates the rate of melting for glaciers and polar ice caps beyond what the historic mean rate has been. Snowfall and rainfall in the rest of the globe are sparser, causing an imbalance in precipitation on the planet. This imbalance is reflected in a rapid increase in the ratio of runoff to ocean evaporation, causing a rise in sea levels. Moreover, ice streams through these areas, a result of meltwater from higher altitudes and seawater from below, are more frequent across the ice sheets. These streams, coupled with high temperatures, cause ice sheets to melt from below, with large chunks breaking off and melting more rapidly than if they remained connected to the continental ice sheets. Common policy questions by jurisdictions facing sea level rise involve identifying the appropriate level of protection. Typical adaptation strategies include a hard infrastructure edge against rising sea levels, which has the following negative impacts: it cuts people off from the ocean, reducing access to a social and cultural amenity, and destroys environmental habitats that are unique to land/ocean interactions.

RESEARCH FORMULATION

The California Coastal Commission and the California Natural Resources Agency, two leading institutions in disseminating scientific findings on climate change and the California coast, tend to focus on the precise amount of expected sea level rise along the coast. When identifying locations of intervention, jurisdictions tend to look solely at the effect sea level rise will have on the built and natural environment without differentiating between the different types of buildings, or the different qualities of the natural environment, that will be affected.

This research effort proposes that such differences, particularly in building type, are significant in assessing the effect of sea level rise on the California coast. Specifically, it looks at the effect of sea level rise on industry and infrastructure, from wastewater treatment plants to energy production and distribution. Rather than beginning the study by understanding the impact of sea level rise on densely populated cities, the study takes as its initial point of interest those locations where sea level rise is most pronounced and proceeds by seeking to find how those conditions overlap with the presence of industrial production and/or processing.

Part 1: Sea Level Rise and Vulnerabilities in the Northern Region, Middle Region, and Souther Region of the California Coast

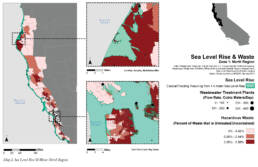

Map 2: Sea level rise is overlaid with waste facility locations, coupled with wastewater vulnerabilities by census tract. In the very north of the California coast there are large areas with a high percentage of untreated and uncontained waste entering the ground. One of the larger wastewater treatment plants falls squarely inside the sea level rise zone. The lower right image focuses on the Bay Area, where large wastewater facilities overlapping with sea level rise are visible.

Map 3: Energy facilities are categorized by type, and tend to be relatively safe throughout the northern region, with the exception of a gas facility in the far north and in the Bay Area.

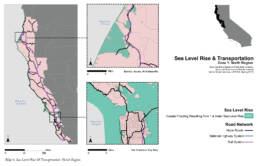

Map 4: Substantial portions of the rail system and major roads in the far north are affected, and less so in the Bay Area with the exception of the San Francisco’s Lake Merced.

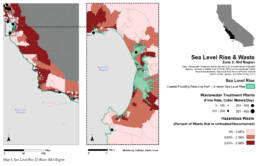

Map 5: Here, one area is particularly affected by sea level rise, and that is from Santa Cruz down to Monterey. All large wastewater treatment plants are affected in this region by sea level rise.

Map 6: Three of five energy facilities in this region affected by sea level rise, and notably two of those are involved with biomass, which require large areas of land for energy production.

Map 7: A substantial portion of rail and highway will be affected by sea level rise in this region.

Map 8: The areas that are most affected in the south, in terms of the extent of sea level rise, coincide with major cities: Los Angeles and San Diego. Two relatively large, in terms of daily flow, wastewater treatment plants are affected by sea level rise, one in Los Angeles and the other in San Diego.

Map 9: The largest concentration of energy production along the California Coast is clearly in the southern tip. Log Angeles, in particular, has a very high number of energy facilities throughout its region. Most of the facilities in Los Angeles are gas ones, which supply the largest amount of energy to the city, and are especially vulnerable in Long Beach, Huntington Beach and Newport Beach.

Map 10: In both the Los Angeles and San Diego regions the major roads along the coast, the scenic routes, are affected by sea level rise.

Part 2: Sea Level Rise and Vulnerabilities in the San Francisco Bay Area

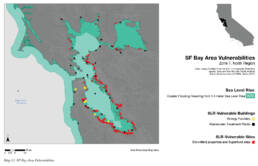

Map 11: To understand the data shown in the maps in Part 1 above, potentially toxic sites involving waste and energy industries were added with other vulnerable landscapes in terms of toxicity (from US EPA and CalEnviroScreen data) to create an index of sea level rise vulnerabilities. A single hotspot emerges from this data, that of the San Francisco Bay Area.

Map 12: Energy facilities and wastewater plants, along with brownfield properties and superfund sites, are shown here. The Bay Area has a high concentration of such sites because of its involvement with the US military and navy throughout the early and mid 20th century. It also has a heavy industrial past.

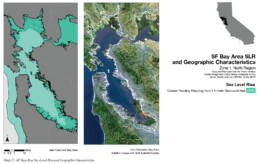

Map 13: Another aspect of the Bay Area to consider, related to sea level rise, is its vulnerability to sudden storm surges and flood. Flood zones correspond almost perfectly with sea level rise but also shows additional vulnerabilities further inland, possibly due to the river pathways and broader watershed system.

Map 14: Equally important is to look at the geographic characteristics that are unique to the Bay Area. Low-lying areas are entirely inundated in a 1.4 meter sea level rise scenario, and a large amount of coastal marshland is jeopardized, important for ecologies that thrive on land/water interactions.

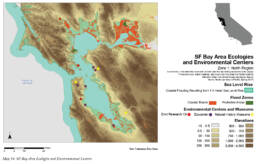

To mobilize adaptation and resilience planning, public awareness needs attention as does research into the particular geographies that make the bay area unique – and so it was important to also map the Environmental and Research Centers and Natural History Museums that have an environmental component to see if their locations bring people closer to areas of high vulnerability.

Map 15: To better understand how sea level rise overlaps with the physical characteristics of the Bay Area, the extents of sea level rise are shown as a white line on the satellite image on the right. The majority of the Bay Area that is affected by sea level is either urban (East, West, and South portions of the bay) or marshland (North area of the bay.)

GEOGRAPHIC AND ATTRIBUTE DATA SOURCES

This study focuses on wastewater treatment plants, energy production, transportation networks, and locations of hazardous waste as well as other vulnerable sites, including superfund and brownfield ones. In addition, it looks at the geographic characteristics of the San Francisco Bay Area, identified through the research presented here as the most vulnerable region along the California coast in the face of sea level rise. Public awareness, key in mobilizing adaptation and resilience planning, is addressed in this study by mapping public research institutions related to environmental studies. Research into the particular geographies that make the Bay Area unique, such as the presence of wetlands and marshes, is also included.

METHODOLOGIES

This study assumes a 1.4 meter sea level rise throughout. It begins with an initial assessment of the overlap between sea level rise and various factors related to industry, identified as follows:

- Wastewater treatment plants (and accompanying flow rate in cubic meters per day)

- Hazardous waste census tracts (as a percent of waste per tract that is untreated or uncontained)

- Energy facilities (categorized by energy type)

- Transportation networks (national highways, major roads, and rail systems)

An index was derived by including the industry listed above coupled with the location of superfund and brownfield properties. This index identifies the San Francisco Bay Area as the most vulnerable site in the face of sea level rise. The Bay Area has a particularly high concentration of vulnerable sites because of its involvement with the U.S. military and navy throughout the early and mid-20th century, coupled with its heavy industrial past.

The latter half of the research in this study focused on the Bay Area, focusing on the following:

- Vulnerability to sudden storm surges, by proxy of FEMA-identified flood zones

- Flood preparedness, by proxy of emergency facility locations (fire & police stations, hospitals)

- Specific geographic characteristics, including marshland and wetland areas

- Public outreach, by proxy of environmental research centers and natural history museums

WHAT DOES ALL THIS MEAN?

Sea level rise affects the California coast in different ways, particularly when comparing the Northern and Southern portions, given the distinct geographic characteristics of each. This study aims to locate those coastal regions where action should be prioritized. It does so by adding to existing literature which determines the location of such hotspots as those most populated by people or whose economic cost of rebuilding is highest. Instead, this report focuses on industry production and distribution, along with existing land vulnerabilities related to toxicity and pollution to make its assessment.

Strategies currently underway in the Bay Area to address sea level rise range from hard infrastructure responses to a more delicate combination of protecting and restoring wetlands combined with building an active defense against rising waters. Such designs, however, are focused on smaller scale, neighborhood-level, interventions. The research here proposes to add the following important question to the existing list of policy responses to sea level rise: what is the appropriate scale of intervention? By looking at a region in addition to a neighborhood, the reshaping of the coastal landscape can move beyond a piecemeal assessment to a more unified set of design efforts. To do so, policies that focus on enabling regional collaborations that can bridge environmental and social relations to coastal habitat are necessary.